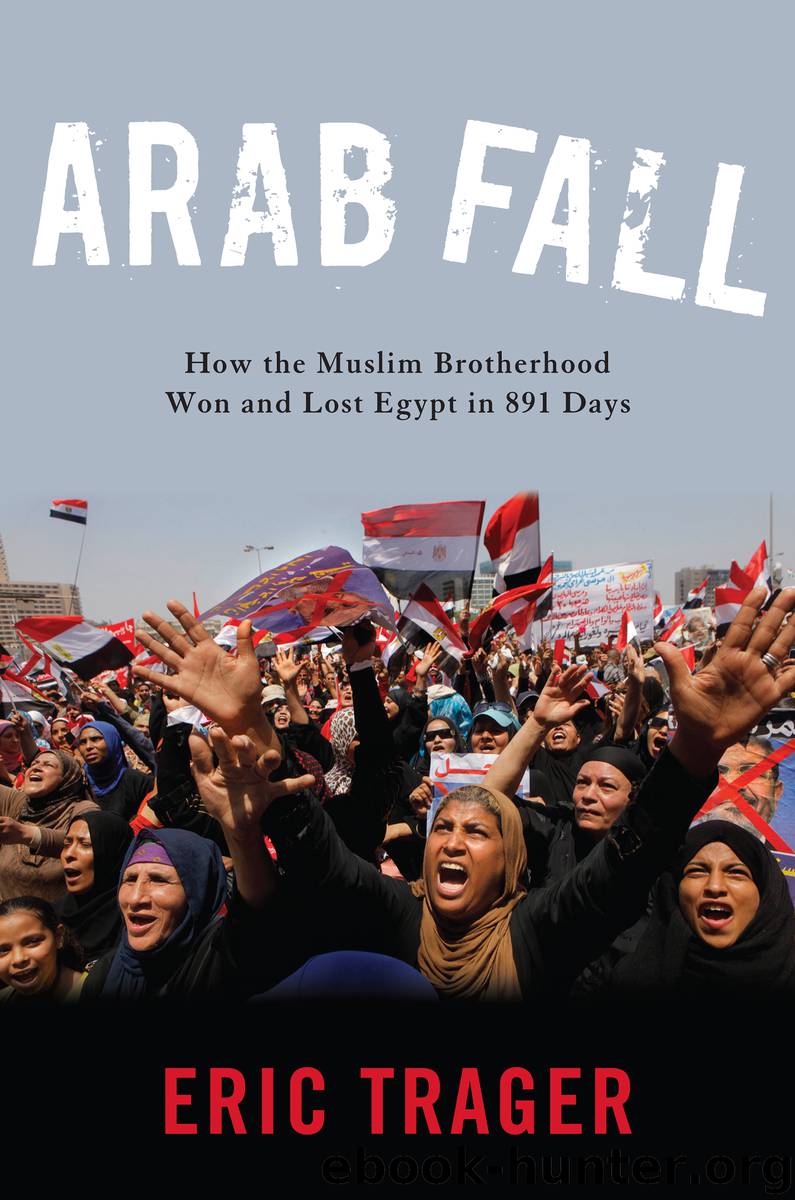

Arab Fall by Trager Eric;

Author:Trager, Eric;

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 4711806

Publisher: Georgetown University Press

Published: 2016-10-04T16:00:00+00:00

10

The Power Grab

* * *

On the evening of November 21, 2012, Mohamed Morsi was a highly respected world leader, widely praised for his pragmatism during the Gaza conflict. But within twenty-four hours, that perception radically changed.

On the afternoon of November 22, Morsi suddenly issued a new constitutional declaration granting himself virtually unchecked power. Of course, he had already asserted total executive and legislative authority through his August 12 declaration, which coincided with his firing of SCAF leaders Tantawi and Anan. But the new declaration removed the last legal check on his power by placing all of his presidential actions above judicial scrutiny.

Specifically the declaration mandated that all of Morsi’s constitutional declarations were “final and binding and cannot be appealed by any way or to any entity” and ruled that all pending legal challenges to his previous declarations were “annulled.” It further empowered Morsi to appoint a new prosecutor-general to a four-year term, thereby circumventing laws that protected the prosecutor from presidential interference. Finally, the declaration empowered Morsi to “take the necessary actions and measures to protect the country and the goals of the revolution”—a broad clause that effectively granted him the authority to do anything.

The declaration directly impinged on the judiciary’s authority in two additional ways. First, it mandated that the judicial branch reopen investigations and prosecutions into cases of murder, attempted murder, and wounding of revolutionaries by “anyone who held a political or executive position under the former regime.” Insofar as this was a presidential order to the judicial branch, it blatantly contradicted the principle of judicial independence. Second, Morsi’s constitutional declaration asserted that “no judicial body” could dissolve the Shura Council, which was the Brotherhood-dominated upper house of Parliament, or the Constituent Assembly, which the Brotherhood-dominated People’s Assembly had appointed before it was dissolved in June.1

Those who defended Morsi’s declaration often focused on this final aspect of it. Morsi, they argued, was merely trying to prevent the judiciary from dissolving the Constituent Assembly, which was drafting Egypt’s new constitution. After all, in October, the SCC started reviewing dozens of lawsuits against the assembly, which alleged that it had been selected unconstitutionally and did not sufficiently reflect the diversity of Egyptian society. And given that the judiciary had ruled to dissolve the first Constituent Assembly in April and the People’s Assembly in June, Morsi had every reason to believe that the SCC would now dissolve the current Constituent Assembly as well.2

Yet this defense of Morsi’s constitutional declaration, which the Brotherhood and its apologists offered repeatedly during the ensuing crisis, ignores some inconvenient facts. For starters, while the judiciary was an institutional barrier to Morsi and the Brotherhood in many instances, it was not an implacable enemy. The judiciary, after all, had supervised every post-Mubarak election, which the Brotherhood’s candidates won overwhelmingly. The judiciary also administered Morsi’s presidential oath. And contrary to the Brotherhood’s depiction of the judiciary as a pro-Mubarak entity, the judiciary contained many individuals who were sympathetic to the Brotherhood, including the judges whom Morsi appointed as his vice president and justice minister.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Buddhism | Christianity |

| Ethnic & Tribal | General |

| Hinduism | Islam |

| Judaism | New Age, Mythology & Occult |

| Religion, Politics & State |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32081)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31471)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31425)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18236)

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14002)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(12821)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(11642)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5131)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4972)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4853)

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Yuval Noah Harari(4696)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(4520)

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl(4302)

The Silk Roads by Peter Frankopan(4279)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4119)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4028)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3804)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3801)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(3797)